Training Paces and Workout Types

How do coaches decide what types of workouts you, our runners, should be doing, and how fast you should be running them? Read on for a primer on training paces and workout types.

It all starts with a physiologic parameter called VO2 Max. This is the maximal rate at which your body can take in and use oxygen during exercise. VO2 Max is an important and reliable indicator of your current level of fitness. With some exceptions, the higher your VO2 Max, the fitter you are.

VO2 Max can be measured in an exercise physiology lab using machines like a metabolic cart. It is reported as milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram of body weight per minute.

If you don’t have a met cart readily available – and most of us don’t – you can approximate your VO2 Max by measuring your time during an all-out running effort of 10 to 15 minutes (about 3K or 2 miles). You can then plug your finishing time into one of the many online calculators that also use other variables like your body weight and your sex to estimate your VO2 Max.

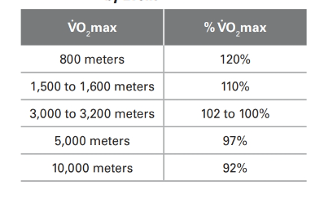

Below is a table from the USATF Coaches’ Handbook that shows the percent of your VO2 max required for different common race distances:

How does this translate to training paces?

Your easy runs, which are entirely aerobic (requiring oxygen), should be run at about 50-55% of your maximal effort. So, for example, if you ran a 2-mile time trial in 14 minutes (7 min/mile pace), it would be very reasonable to run your easy runs at a 9 to 10 min/mile pace. You want to keep your hard days hard and your easy days easy. Running significantly slower than what you are capable of allows you to put some needed miles on your legs without taxing your body excessively.

Two workout types that require a significant amount of oxygen and that help develop your speed endurance are Aerobic Threshold runs (done at 65-75% of max effort) and Lactate Threshold runs (done at 85% of max effort).

Aerobic threshold runs are run slightly faster than your easy pace (I call this a “plus pace”). A good rule of thumb to calculate the right pace for this type of workout is to add 45 to 60 seconds to your 5K race pace. You might also target this pace if you are training to run a marathon. A typical workout would be a longer tempo run of 45 minutes to an hour.

Lactate threshold runs are run at a pace that is 25 to 30 seconds slower than your 5K race pace. These are typically either a strong 20–30-minute bout of continuous running, or long repeats (5-10 minutes or 1 to 2 miles) with short rest intervals (no more than 20% of the total run time). Because the rest intervals are short, you can’t recover completely. This helps you get used to running faster while you are increasingly fatigued. This workout type is good for developing speed endurance.

A third type of workout, VO2 max intervals, is an opportunity to get used to running at your goal 5K or 3K race pace. These workouts involve 2-to-5-minute intervals run at 90-100% effort, with long recovery times (typically 50-100% of total run time). This workout type develops your ability to run at a faster pace.

Even if you are a long-distance runner, you will need to spend some time working on your sprint mechanics and ability. Starts and surges both require sprinting and a good finishing kick at the end of the race certainly comes in handy and is an important tool. I recommend you include both 6-10 second hard efforts (utilizing your alactic energy system), and 10-90 second hard efforts (utilizing your glycolytic energy system) in your training at least 1-2 times per week.

The following diagram illustrates a tried-and-true training progression for endurance events:

Build your aerobic base by including a period in your training where you are primarily doing easy runs and long runs. Then, in your pre-competitive and early competitive cycles, incorporate aerobic and lactate threshold work. In your competitive season, develop your acidosis tolerance with intervals and repetitions. Continue to work on your biomotor abilities – acceleration, speed, power, mobility and strength – throughout your training.